The best advice I was ever offered – from the best pilot I ever flew with

The best advice I was ever offered – from the best pilot I ever flew with.

If you have ever read the epic ‘Fate is the Hunter‘, by Captain Ernest K Gann, you will recall the respect, even reverence, that the author felt for his early mentor, a certain Captain Ross.

The then First Officer Gann inadvertently and prematurely retracted the landing gear of their Douglas DC-2, prior to lift-off! The experienced captain was able to retrieve this critical situation: Accelerating the crippled airplane in ‘ground effect’ (a cushion of air, compressed by the close proximity of the wing to the ground), Ross skillfully manages to remain airborne at very low airspeed, somehow preventing the propeller tips from striking the ground while the gear retracts under them, before climbing away, safely. Just imagine being that in that situation, let alone being the cause!

Feeling utterly sick, Gann cannot imagine what the captain will say when he settles down on track and completes the after take-off checklist: and his pulse returns to normal. Quite naturally, he anticipates an abrupt end to his embryonic airline career, when Captain Ross files the inevitable flight report.

The captain’s considered and dry response? “If you ever do that to me again, I will cut you out of my will!” What a wonderful comeback and relief: and what an airman was Ross.

Well, Captain Geoffrey W Lushey DFM was my Captain Ross. Fortunately, I had already gained from Ernest Gann’s near-disastrous folly: I didn’t emulate that particular sin, but I still had so much to learn…

This is the second article in a planned occasional series, sharing some of the most memorable and treasured experiences. This one is also from my own career: We do plan to feature other, highly esteemed pilot friends and colleagues, who are only too willing to share their collective aviation experience. The crucial lessons that we learned along the way are just as valid today. They contribute, in no small way, to that intangible but essential quality known in aviation as ‘airmanship’.

Preface

This true story is recounted in the hope that it might benefit younger pilots, whether they be professional or recreational; for the lessons I learned are at once ageless and matchless.

My airline career began on 12 January 1970, after l had Ianded my dream job with Trans-Australia Airlines – TAA, as a trainee First Officer.

My first airline aircraft, in fact my first ‘real’ twin-engine aircraft apart from the Cessna 337 centre-line thrust ‘push-pull ‘ twin, was the Fokker F27 Friendship. It was a huge leap from 4300lbs max TO weight and twin 210HP engines in the Cessna, to 43,500lbs max TO weight and twin 2000HP Rolls Royce Dart turboprop engines. It was also a beautiful first airliner: Not hard to fly, but hard to fly well, with the huge increase in inertia especially noticeable, from that 10-fold difference in weight.

I had been accepted by TAA, with 1735 hrs in my logbook, not too bad for a 22-yo in those days; but: I had no instrument rating, not even a night visual flight rating and I had logged just 20hrs’ instrument flight time and 18hrs at night! My professional flight experience to that point, post PPL and CPL training which began in 1965, had been mostly flight instruction by day, in single-engine aircraft: Cessna, Auster (450 hours), Beechcraft and a glorious 50-odd hrs in the ubiquitous DH-82a Tiger Moth biplane. The ‘Tiger‘ and the Austers were started by hand-swinging the propellers – very basic, but so rewarding when the Gypsy Major engines burst into life – and – I hadn’t lost an arm – or my head!

My new learning curve was almost vertical, as TAA’s world-class instructors, including characters like Bill Coe, Dave Fenwick and Ross Brandie, guided my course cohort of 17 pilots through the gas turbine engineering course, followed by the F27 engineering, emergency procedures and instrument rating courses: All very thorough. These brilliant engineers and others later on, such as Dave Axxon, became our technical guides and mentors, forever. There was nothing they didn’t know about their aircraft. There were 4 other pilots – experienced DC-3 and Vickers Viscount captains – on our course – Captains Col Tiller, Ivan East (also a part-time male model and Australia’s ‘Marlboro (cigarettes) Man‘), Jim Betts and Mal McDougall, all of whom I had the privilege and pleasure to crew with, later.

A vital hint that I should have embraced, totally

During the course, Col and Ivan missed a school day while they completed their licence renewal base flying checks on the Viscount, at Mangalore VIC. When they returned next day, we asked them all about these renewal check requirements and processes, as a company check and training system was new to most of us. Col Tiller, a highly intelligent and perceptive pilot, replied, “When you pass a check, it only means you’ve been operating safely for the last 6 months: it has no bearing, whatsoever on the next 6. On the other hand, if you fail a check, you haven’t just had a bad day: you’ve been unsafe for the last 6 months!”

Great advice but, in retrospect, I really wish I had applied it more diligently. It would have helped me, considerably, as things turned out.

We completed the F27 conversion in actual aircraft, as TAA didn’t ever possess a F27 full-flight simulator – only fixed-base trainers, for engineering and procedural training, one of which was an ex-Qantas fixed-base analogue Lockheed Constellation simulator, semi-converted as a F27. I had wanted to fly the beautiful F27, ever since flying from Melbourne to our nation’s capital, Canberra, on a day-return high school year-7 excursion, just 11 years earlier, in a Mk 1 series Friendship, registered VH-TFF. It turned out that this same aeroplane happened to be the very second F27 that I ever flew! A particularly proud moment.

David’s image of F27-100 VH-TFF, taken at Canberra ACT on the 1959 school excursion.

David’s image of F27-100 VH-TFF, taken at Canberra ACT on the 1959 school excursion.

Following my F27 base conversion, conducted by the highly capable Captain Alan Judd (a former RAAF Dakota pilot), I then commenced my line training with a wonderful character, Captain Noel Knappstein (a former RAN Fleet Air Arm Sea Fury pilot).

Our first line ‘pattern‘ of flying took us up the ‘track’: On the first day, we flew from Essendon to Adelaide SA, Leigh Creek SA and Alice Springs NT, where we over-nighted. Next day: Alice to Tennant Creek, RAAF Tindal (near Katherine, NT) and on to Darwin. On the third day, we operated an international charter flight (on behalf of Qantas) to (the then) Portuguese Timor (now East Timor) and return to Darwin. And, on the final day, we flew Darwin to Tindal, Tennant Creek and Adelaide, before ‘dead-heading’ (passengering) home to Essendon.

The rest of my line training was equally challenging, but Noel Knappstein was a great training captain and I passed my final check to the line with the then F27 Fleet/Training Captain, Atholl Fraser, on 27 July 1970. At 23-yrs, I was now a fully qualified, single-striped F27 First Officer and I was thrown now into full-time line operations, the love of which has remained with me, ever since: real aircraft, real-time weather, real passengers and real-time events, not a scripted training exercise.

My first licence renewal check: A very bad dream: 16 September 1970

The months flew by and suddenly, my September roster indicated my first licence renewal check was approaching. I had about 3 weeks to prepare for a base flying check at Mangalore, north of Melbourne and just over the Great Dividing Range. It had been, for many years, the trusty alternate aerodrome for Essendon and was, sadly, the location of the training accident on 31 October 1954, that resulted in the loss of TAA’s first Viscount, VH-TVA and 3 crew members. One crew member survived: FO George McDougall (a former RAAF Liberator captain and no relation to Mal McDougall) was standing in the flight deck, behind the 2 pilots, when a simulated double engine failure (on the same side) asymmetric exercise went terribly wrong.

The wing was almost vertical at about 300ft AGL, when 38-yo George bolted for the aft cabin and wedged himself behind the last row of seats: and survived, although his hair turned snowy white, overnight. (He even survived flying with me, years later, on the B727: (I think I can recall him saying: “My hair cannot possibly get any whiter!”)

On 16 September 1970, 5 or 6 pilots, including myself, were briefed by Captain Geoff Lushey, the new F27 Fleet/Training Manager. A former RAAF Mustang and Meteor sergeant/pilot, Geoff had been awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal – DFM, while serving in Korea. He was tall and slim, with a passing resemblance (I thought) to one of my favourite actors, Gregory Peck. His demeanour was both impressive and imposing and already he had a reputation for demanding high standards from his licence renewal ‘checkees’. We had not met, previously.

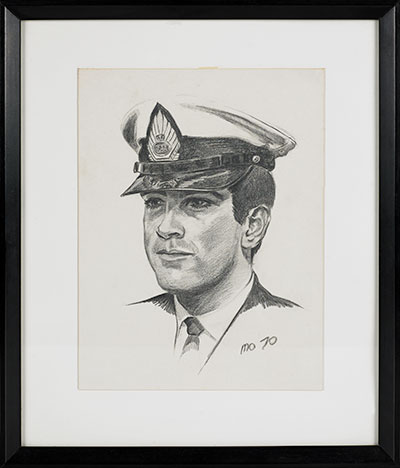

Sgt Pilot Geoff Lushey DFM

My comfort zone rapidly evaporated as the briefing continued. I had a sinking feeling, as I realised that I hadn’t fully followed Col Tiller’s sage advice, 6 months earlier. (I was NOT nearly well-enough prepared for this check, today. I knew I was in trouble and it was my fault, entirely.)

Seated next to Captain Lushey in the F27 at Mangalore, it was finally my turn now to perform a range of aviation miracles, mandated by the Non-Normal checklists: engine shut-downs and re-lights, simulated engine failure and feather drills and all the rest of the base renewal check requirements. I had studied everything BUT the finer points of these extremely challenging non-normal exercises.

On this occasion, I couldn’t fly for nuts! I was doing dopey things like calling “Flaps UP”, following a simulated engine failure, without first checking that I had sufficient airspeed and other very basic errors. Nor was I able to put each error behind me and concentrate on the next ‘hurdle‘. Everything I stuffed up was compounding. Finally, Captain Lushey looked across at me, smiled grimly and said, clearly disappointed with my performance, “I don’t think this is going to get any better, today, do you? You’d better get out of your seat and give it to someone who CAN fly an aeroplane .”

Feeling utterly sick, just like Ernest Gann had, years earlier, I completely ignored my fellow checkees as I vacated the flight deck and sank into the last row of passenger seats, totally distraught; almost in tears, angry and frustrated: but only with myself and my dismal performance, certainly not the captain. Just like Ernest K Gann had described, I couldn’t imagine what this impressive captain who, I had been told, suffered fools badly, would say when he debriefed me later, back at Essendon. I just had to wait while the last several pilots demonstrated their proficiency in the base-flying skills, before, mercifully, the F27 turned for home. (I prayed that I would simply wake up and my nightmare would be over): I knew my employment could and likely would be terminated, for it had been emphasised, during all the earlier courses, that we junior FOs were on probation for the first 2 years. My brilliant airline career was clearly going to be history, very soon.

In a company briefing room, safely back at the Essendon terminal, Captain Lushey debriefed everyone else, signed their licence renewal documents and dismissed them, back to the line. They’d all passed, with flying colours, literally. Then, he turned to me, for the first time since I’d vacated the RH seat at Mangalore and said, “Let’s go down to my office.” My recollection is that we walked in silence, down to the separate wing of TAA executive offices, known colloquially as the Cathedral, where I gratefully accepted his offer of a cup of hot coffee. Then, we sat down, either side of his desk.

“Now, son”, he began, “Can you really fly an aeroplane?” “Yes, I can“, I replied. “Well”, he continued, “I saw no evidence of that, today.” “Frankly, neither did I!“, I offered. He smiled and seemed relieved that I had already self-assessed my own dismal performance and he seemed to relaxed a little. (As an experienced flight instructor, at least I knew how to assess myself.) He enquired if there were any human factors or issues, marital worries or other concerns that might have contributed to my performance on this day and I replied in the negative.

He then enquired, “OK, then what just happened at Mangalore today?” “I replied, “I just didn’t know what I didn’t know.” He asked, gently, “Do you know, now?” “Yes“, I said. With that, he smiled and produced a company licence renewal check report form and signed it, after inscribing something brief. Then he asked me to read and endorse it: ‘MINIMUM COMPANY STANDARD‘: He had passed me. I was only too pleased to sign the form. Frankly, I would have failed me!

Then, he became serious again, looking me straight in the eye: “Son, you and I are going flying for 2-3 days next week on the line and it better be good! Crewing will contact you with the details.”

The 2-day route check was scheduled for 26-27 September 1970. Starting out of Sydney, we were to operate 2 return flights to Canberra and back to Sydney on the first day. Plenty of opportunities to either stuff-up, again, or to quietly impress: it had to be the latter. Since I had officially ‘passed’ my base check, I was still able to fly in the interim period with other captains, one of whom was another check captain, so I sought his counsel and asked for any constructive feedback he could offer, regarding all aspects of my operation – either as pilot flying or pilot not flying, i.e., supporting. He offered a few good tips and I noted them carefully. I also had a few days off, to study – everything – and I did.

David Jacobson – a sketch from 1970

The 2-day route check: My get-out-of-jail- card: 26-27 September 1970

Geoff and I – it was Geoff and David, now – were deadheading to Sydney on September 26th and there was now an opportunity to start to get to know each other a little and to discuss the day’s flying, the likely weather and other operational considerations, ahead of launching into it. He made no mention, whatsoever, of our last flight together. After flight planning, we located, checked and boarded the aircraft on the tarmac. The first leg to Canberra was flown by Geoff, as management pilots flew few personal sectors, themselves, due the dual workloads of admin and checking duties. His flying was impeccable, yet spirited and I recall thinking that I had a very hard act to follow, on my first return leg to Sydney.

After a couple of very pleasant hours in his company, I had relaxed just a little and that helped; I was content with the flight from Canberra, so far, as we began our descent into Sydney. Our arrival was straight in from a VOR radio beacon at Bindook, in the Blue Mountains, onto runway 07 (aligned nearly east – 068ºM), which had been reported as ‘damp‘. Regardless of the surface winds at Sydney Airport, I knew that we would have a likely prevailing tailwind of about 40kts (80km/hr), behind us. There was also the likelihood of ATC asking us for our best (highest) descent speed, to maintain separation from any faster, following jets. As pilot flying (PF), I planned and began the descent slightly earlier than I might have, normally: It paid off.

We were maintaining our usual maximum indicated airspeed: 210kts IAS on the descent, when ATC called us and requested our ‘best-speed-as-long-as-possible‘, as they had one of the then–very-new-and-very-large KLM B747 Jumbos behind us, following in sequence. Although normally much faster than us, ATC had already reduced that aircraft back to 250kts IAS, but the gap between us would still have been closing, with the 40kt difference in IAS.

Geoff acknowledged the call and looked at me, studying my reaction. I was comfortable and quietly confident: we were already at maximum speed and I had some spare distance up my sleeve, to help facilitate our reduction in speed for the approach, when the time came. The 747 was ATC’s problem, not mine. However, I was still computing how I was going to manage the situation, given the tailwind and the extra groundspeed it created.

Normally, ATC would clear us down no lower than 3000ft at Glenfield NDB, 10nm on final, for the 07 straight-in instrument landing system – ILS. On this day, ATC very helpfully cleared us down to 2000ft at 10nm, which I knew would assist me in slowing the F27 from our present 210kts IAS back to 168kts (the maximum extension speed for the landing gear, our first decent drag-reducing device) in level flight at 2000ft, before intercepting the 3º ILS glideslope from beneath and then starting our final approach.

We levelled off at 2000ft and I capitalised on not having to decelerate whilst also descending. The F27 was a very ‘clean‘ (slippery) aircraft to slow down quickly, as it didn’t have a speedbrake, like the jets and modern turboprop aircraft. The laws of physics needed time, but I needed to be back to 168kts by the time we intercepted the ILS glideslope and started down again from 2000ft, at about 6nm, so I could use the added drag from the landing gear to decelerate further to our next target airspeed, 144kts, and start extending some flaps; and then to 126kts, so we could reduce further back to our final (runway) target threshold speed – TTS. To make things a little more challenging, the F27 had no groundspeed indication.

However, the aircraft needed further help to slow down. So I took a chance and made a somewhat contentious decision: At about 8nm out (without first seeking Geoff’s approval, nor forgetting for a second that he was the F27 Fleet manager), I closed both power levers (throttles), smoothly and fully, against the recommended and normal procedure of maintaining a minimum power setting of 40psi of torque. (This company requirement was stipulated to reduce propeller layshaft shuttling, causing excessive wear and tear, which occurred at lower power settings. But I had read a Company bulletin, noting that the aircraft manufacturers, Fokker, had published advice that flight crew could obtain some instant drag – only if necessary – without hurting the props – by fully closing the throttles completely and loading the layshafts the other way.) We were now a 20-tonne glider.

I felt, rather than saw Geoff’s eyebrows raise and his eyes narrow, but he said nothing. Neither did I: I was content, maintaining the 3º glideslope, perfectly: the airspeed was reducing well and I called for landing flap 40º and the landing checklist. ATC cleared us to land. The wind on runway 07 was actually a 15kt full crosswind, so still no headwind component to help reduce the groundspeed and there was the further consideration of the requirement for the judicious application of aileron and rudder inputs, to offset the L sideways drift, generated by the southerly crosswind, off Botany Bay. I never did advance the throttles from their idle stops.

The airspeed finally drifted back to our TTS of about 85kts, just prior to commencing the landing flare and I completed a full deadstick (idle-power), perfect touchdown on the windward (RH) main wheels first, then the LH main gear, finally lowering the nosewheel gently onto the damp runway. At 40kts IAS, I selected ground fine (0º pitch angle) on the propellers (a retarding effect similar to reverse thrust) and applied only slight pneumatic wheel braking. As we turned off the runway, I first heard and then saw the KLM 747 in full reverse thrust, raising much surface water as it rolled through after touching down only just behind us. We had honoured our commitment to ATC for ‘best-speed-as-long-as-possible‘ and the huge 747 hadn’t had to go around!

We swapped roles: Geoff taxied the aircraft after I obtained a taxy clearance to our parking bay on the TAA tarmac. As we taxied in, Geoff enquired, with a broad grin: “Are you the same guy I was with at Mangalore, last week?” I replied, “I’m afraid so.” He then offered a huge compliment: “I know a lot of captains who couldn’t have pulled that off!” I was just elated: Finally, I had scored some points on the board. We shut down and parted, briefly, as we prepared for the return sector to Canberra. The turnaround time was about 30 minutes and, after our traffic and engineering staff had cleared us, we started the engines again and taxied out for a departure to the south, on Sydney’s main north/south runway 16 (156ºM). We had a short dream run (no other traffic) to the take-off holding point and were cleared for take-off, before we even had to stop there. Geoff was again the pilot flying.

Geoff’s take-off and climb out over Botany Bay was perfectly normal: Until: I started to perform a normal geographic visual scan of every control, switch and instrument panel indication. On the LH overhead panel, above Geoff’s head, were 2 illuminated RED alternator failure warning lights. (‘Hang on, the alternators are completely separate animals: there cannot be a double alternator failure, can there?? – I was asking myself. In the F27, the alternators supplied 208V AC to power the windscreen heat, wing and tail de-icing and engine nacelle and propeller anti-icing systems and some extra heating panels in the cockpit floor.)

Then I froze: My eyes had shifted to the 2 alternator switches – and BOTH were still in the OFF position. Then, the penny dropped: The alternators had NOT failed: They had not been turned ON at all, after we started the engines and neither of us picked that up because, in our haste to depart on time, we hadn’t completed the after-start checklist! Geoff had been distracted by something and I had failed to perform my primary support role as First Officer and remind him (something like, ‘Geoff, would you like an after-start checklist”. ‘Oh GREAT WORK, Jacobson!’ After that glorious approach and landing, you’ve just blown all your points and gone back to square one! But I couldn’t reflect or chastise myself any longer: Not now, anyway.) There was only one thing to do:

I spoke directly and clearly across the flight deck: “Geoff, I’m not sure we completed the after start checklist.” He raised an eyebrow and asked, “Why do you say that?” I just pointed to the panel above his head. The autopilot was by now flying the aircraft. He tilted his head and his eyes fell on the 2 RED alternator lights. Then they focused onto the switches. He turned back to me and said, very calmly, “Can I offer you a little piece of advice?” (I had no idea what he was going to say, BUT, at this absolutely critical stage of my pathetic airline career, I certainly wasn’t about to say, “No, thank you.”)

“It doesn’t matter when something goes wrong: What matters is what you do, when it does.”

With that, he returned his eyes to the offending panel and turned the 2 alternator switches ON. The 2 red lights extinguished. He turned back to his primary role – flying and managing the aircraft – and the matter was never mentioned again. Until now.

The rest of that sector went well, as did the following day. We flew from Sydney to Canberra again, then on to Essendon, Wynyard TAS and finally back to Essendon. Geoff debriefed me in his office, once again: very favorably and generously and I resumed my learning curve: one that hasn’t stopped, yet, even though I am no longer flying actively.

David’s logbook entries for September 1970

Captain Geoff Lushey gave me both the opportunity to save my career from oblivion and that best single piece of advice, I ever received. We went on to fly the DC-9 and the B727 together. He subsequently taught me many more things about what is and what is not a fair thing to do, in a jet. More than any other captain, he challenged me to keep improving, every single time we went flying together, without ever turning our operation into a competition.

I have been reminded recently, by another highly respected colleague, how Geoff always made his first officers feel that they were part of a team. In this regard, he was way ahead of his time in introducing cockpit resource management (CRM) principles that are part of standard aircrew training, today. I know many of us later modeled much of our own operation, as captains ourselves, from the examples he demonstrated. It almost goes without saying that his own personal flying was impeccable. He could fly a fully inverted instrument circuit, in the DC-9-30 simulator (with the motion turned off, to protect the sim), all within command instrument rating control tolerances! It took me all my instrument flying skill to perform the same manoeuvre, upright!

Captain Geoffrey W Lushey DFM

Of course, long retired now, Captain Geoff Lushey remains, to this day, the single best pilot and finest airman with whom I ever had the privilege and pleasure to fly. There were many other inspirational pilots, of course, but Geoff was the stand-out.

It is no overstatement to say that I owe him my career and I am grateful to have had still, all these years later, the opportunity to say so: and for Geoff to have been able to read and endorse my version of these events!

Wishing you many safe landings

Captain David M Jacobson FRAeS MAP

Would you care to experience that unsurpassed sense of accomplishment, derived from executing consistently beautiful landings, more often?

For starters, Download the FREE Jacobson Flare LITE, our no fuss/no frills introduction. Here we demonstrate, step by step, the application of the Jacobson Flare on a typical grass airstrip at Porepunkah, YPOK.

We invite you to browse the consistently positive comments on our Testimonials page. Many pilots, of all levels of experience, have downloaded our Apps. Read about their own experiences with the Jacobson Flare technique and the App.

Then download the COMPLETE Jacobson Flare app – for iOS. You’re already possibly paying $300+/hour to hire an aeroplane: You’ll recover the cost of the app, in just ONE LESS-NEEDED CIRCUIT. Moreover, you’ll have an invaluable reference tool, throughout your entire life in aviation.

Download the COMPLETE Jacobson Flare App for iOS devices now.

We invite you, also, to review our new, FREE companion app,

offering a convenient way of staying abreast of our latest blogs.

Download the Jacobson Flare NEWS App for iOS devices now.